I love being a musician. I love being able to do what I do. My musical schedule keeps me busy and working hard, but I’m truly thankful to have such opportunities. When the opportunities dry up or become sparse, it depresses me. And, conversely, there is nothing else I do with any regularity that I identify so strongly with.

Doing something vs. doing something and bleeding for it are totally different. As an extreme example on the other end, I exercise a few times a week, but take zero pride in it, don’t enjoy it, and don’t give a shit at all about it. It’s strictly a chore. I show up in the gym looking unkempt and like a homeless person while others who care about such matters wear their fancy gym clothes and seem to take pride in their role as “gym folks.” I have as much interest in being “identified” as an exercise guy as I do being identified as someone who folds laundry.

But music is who I am and what I do. I like when people know that I’m a music guy. My identity is wrapped in it.

Of course, it’s great fun. Of course, it’s inspiring and a creative outlet. And it makes people happy, which is always good.

But this past weekend’s show inspired me to take pen to paper—or key to blog—to talk about something else that I noticed. How happy it makes me to be professional enough to be able to handle situations that arise that allow you to get through a gig under less than ideal circumstances.

“A gig is a landmine of sh*t that’s out of your control.”

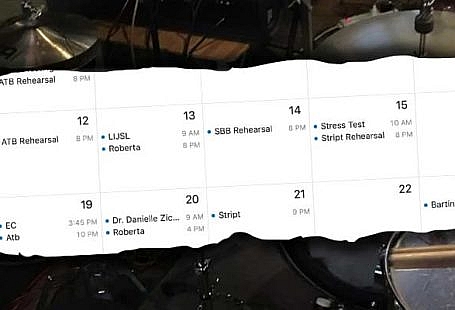

Now, I’ve already talked about how music is not my profession, and lest any of this stuff starts sounding big-headed or self-aggrandizing, I refer you back to the notion that almost all musicians I know walk a treacherous balance beam over a seas equal parts confidence and insecurity. But the interesting thing to note is that, like anything else, practice makes one better at something…. and I’m not talking here about time in the practice room working on musical skills or learning songs… I’m talking about how getting out and gigging 50, 60, or more times a years—as I have been humbly fortunate to do for most of the last decade—makes you better at dealing with unpredictable scenarios that come up on the gig. And let me tell you, there are lots of them…

A gig is a landmine of shit that’s out of your control. When we rehearse, we can control our environment. When you step into a live situation, there are always unknowns. Sound alone, good grief, could be a whole chapter here. How is the monitor situation and the acoustics of the room? Can you hear the others in the band? Can you hear yourself? Are you too loud? Not loud enough?

Then there are owners, time schedules, equipment malfunctions… You could make an entire blog—the blog itself, not one individual entry—about live musical nightmares. Most of us are not the Eagles here, touring with the best equipment money can buy, an entourage of supporting technicians, careful sound checks (we usually don’t get any), and the ability to make demands. We have to blindly jump in and hope for the best. And we’re often doing all this for gas money if we’re lucky… or less.

On this particular weekend’s adventure, I carpooled in with a bandmate, showing up at a new place (new to us) and by the time I got there, not even counting the first piece of stress that there was nowhere to park and no evident clear path to load our gear in, it was evident that there was already some problems that had to be dealt with. Namely, we had a stage area that was way too tiny and a restaurant owner who was more than just a little concerned (freaking out, perhaps one might say) about this.

“Wait, you have five people in your band?” she said with great worry to the guy in the band who booked this. “We only do bands with four at most! We can’t fit five!” Yeah, but your assistant booked us and she knew we had five…

The bandmate booking rep managed to talk her off the ledge by assuring her it would be OK. He said, “Let’s make it work tonight. We’ll get through it. And then for the future, if you don’t think we’re a fit, no worries. But let’s get through tonight. We’ll be fine.”

And then began the act of making good on our promise. We crammed everything in. One guy turned his mic-stand sideways. Another literally stood in the entrance to a closet, using a wireless connection to his guitar amp.

For me, I had to strip down to a drum set with two drums only: my snare drum and bass drum. I play a small-ish kit to begin with, but usually there are at least two tom-toms: one on the bass drum and one on the floor. A standard “four-piece” set up. Now, I had to ditch the rack tom so I could mount my ride cymbal on the bass drum and save floor space, and there also wasn’t enough room to put a floor tom and my microphone stand on the stage. So, besides that I had to “make it work” with a somewhat-different configuration, I also had to put my mic stand and my monitoring stuff to the right of me where the floor tom usually would sit. So what, right? Well, actually, it’s a somewhat significant issue, because I’m totally accustomed to having that stuff on the left. Let me explain further…

Singing and drumming at the same time presents different challenges than other singing instrumentalists have. Among them, we play in a sitting, stationary position, so we can’t just casually move around to step up to our mic. We’re fixed. The mic has to be just where it needs to be and there’s no room for variation. Then, of course, we have to swing our arms around—holding sticks in our hands that make our limbs a foot longer—and the possibility of the mic or mic stand being in the way and getting clobbered is significant. I’ll go as far as to argue that even in the best situation, it is always in the way, period, and the ability to do your job as a drummer and not smack into the boom arm or mic is a skill in itself that gets developed with practice. And my skill in that area is developed “on the left.” I have oodles of experience—physically and ergonomically positioning myself—with that stuff coming in from my left. Conversely, I’ve very little experience with it coming in from my right. That was a challenge I accepted I had to work around.

I mentioned the monitoring stuff, too. My in ear controls—depending on what I’m using—either snap to my belt (on my left) or clip to the mic stand (on my left). Either way, again, my ability to keep a groove going mid-song while reaching over and making adjustments is entirely based on muscle memory working “to the left.” Not so on the right.

So, no, I’m not trying to paint the picture that the issues I had to deal with were ridiculously insurmountable like “Oh, I had to play using my teeth because my arms were in a straitjacket.” They weren’t. But they were added wrinkles that I reasonably-confidently worked around, and that made me feel good about myself. Not because I’m trying to stroke myself here, but because I know full-well that there was a time in my journey where these kind of curve balls would have stressed me out to no end and would have thrown me off my game significantly. Hell, in the beginning years of my playing when I was but a wee drumming pup, just having a drum on the kit set up at a slightly different height or angle would totally screw me up. I remember being 17 and taking measurements with a tape measure and writing them down before breakdown for a gig: “Ok, my snare drum has to be exactly 18 inches off the ground and positioned 4 inches from the hi-hat stand.” I was worried that if I placed it 19 and 5 inches instead that I wouldn’t be able to play without screwing up. I’ve come a long way in 30+ years.

But that “coming a long way” has a lot to do with doing it, and doing it, and doing it, and doing it. You get good when you wash, rinse, and repeat. And that makes me happy—it fuels the pride I have in doing this craft—to think that I have earned my way into the fraternity of people who are capable of dealing with what is thrown at me on a gig without feeling like I need to go throw up first.

That was a more detailed breakdown of my personal story for the evening, but what made it great was that the whole band stepped up. In the end, the show went quite well and the owner was very happy. Carpooling home, my mate and I recapped the evening. I made the comment about how everyone met the challenge, and he noted that a real strength of this particular group is that there were five participants and no one was a “problem child,” as you sometimes have in bands. No one was going to throw a fit or demand that they had to set up their Marshall Full Stack. Everyone understood the concerns of the owner—who has a business to run—and we all worked to make it a success. It’s like we’re all… professionals. Even if we’re not. You can be professional without being a professional. And maybe that makes you a professional of sorts. My mate made this comment in summary: “We’ve been doing this long enough and have enough experience that I think we could hold our own with professionals in a lot of settings, even though we’re technically not (people who do it as our primary source of income). It’s like we’re ‘casually professional.’”

Indeed. “Casually Professional.” I like that. It warms the cockles of my heart to think that could be true. I love what I do.